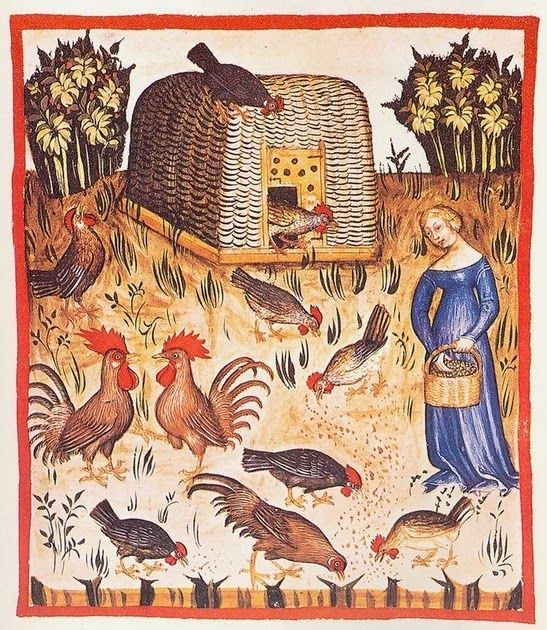

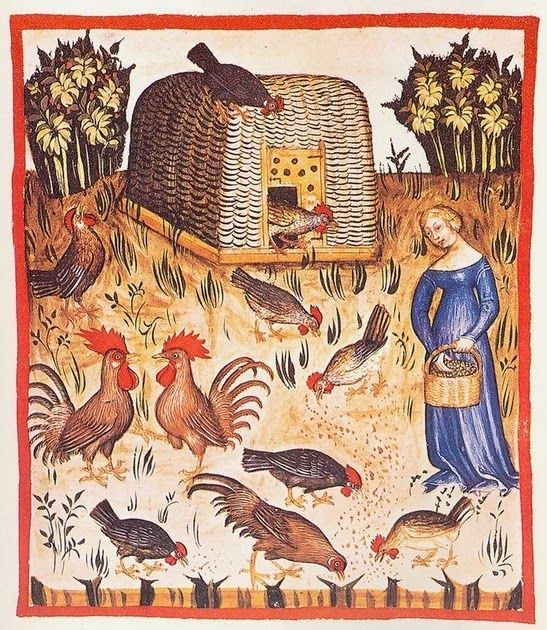

Chicken keeping has a long and successful history, dating back to antiquity. Some 19th century writers would have their readers believe that prior to the Victorian era poultry breeding was not a specialized occupation. It was certainly elevated in status once poultry shows began awarding prizes for quality and for new breeds, but the number of illustrations from the Medieval era indicate raising poultry was quite common (whether for food or sport) and Pliny the Elder wrote that chickens were specifically being bred for the table as early as the Biblical era.

Truly, prior to The American Standard of Perfection, worthy specimens were being bred for various traits such as the following account by Pliny the Elder of hens, cocks and capons bred for the table.

“THEY of the Island Delos began the cramming [force feeding] of Hens and Pullein first. And from them arose that detestable gourmandise and gluttonie to eat Hens and Capons [emasculated rooster] so fat and enterlarded with their owne grease. Among the old statutes ordained for to represse inordinate feasts, I find in one act made by C. Fannius, a Consull of Rome, eleven yeares before the third Punicke warre, an expresse prohibition & restraint, that no man should have his table served with any foule, unlesse it were one Hen, and no more, and the same a runner onely, and not fed up and crammed fat . . . namely, to feed Cockes and Capons also with a past soked in milk & mead together, for to make their flesh more tender, delicate, and of sweeter tast: for that the letter of the statute reached no farther than to Hens or Pullets. As for the Hens, they onley bee thought good and well ynough crammed, which are fat about the necke, and have their skin plumpe and soft there . . . The Parthians also have taught our cooks their own fashions. And yet for all this fine dressing and setting out of meat, there is nothing that pleaseth and contenteth the tooth of man in all respects; whiles one loveth nothing but the leg, another liketh and praiseth the white brawne alone, about the breast bone. The first that devised a Barton and Mue to keepe foule, was M. Lenius Strabo, a gentleman of Rome, who made such as one at Brindis, where he had enclosed birds of all kinds. And by his example we began to keep foules within narrow coupes and cages as prisoners, to which creatures Nature had allowed the wide aire for their scope and habitation.”

Pliny is said to have been ten years old at the time of Jesus’ crucifixion. While no direct quote is found in the Bible regarding domesticating poultry, we know chickens were present. Note in Matthew 23:37, “. . . even as a hen gathereth her chickens under her wings. . .” and, “Before the cock crows today, you will disown me three times,” from John 18:13-27.

At the turn of the 20th century Mr. Harrison Weir wrote, “Old books, Middle Age inventories and other sources make it perfectly plain that whatever may have been told to the contrary, for many centuries our poultry was not merely one of the neglected appendages of the villa and farm, but was chosen and bred with much care, attention and discretion; and that before any poultry shows existed, the table fowls of Kent were noted in history, and with those of Sussex and Surrey were truthfully pronounced by competent judges to be as ‘table fowls the very finest and best in the world.’”

Early settlers certainly brought the best of their fowl with them to the New World and continued to improve the breeds. Eggs are indispensable in the preparation of a wide variety of dishes and chicken recipes abound in historic cookbooks. In working class homes, it is doubtful pullets were butchered as often as hens unless the hatch was very good. Spare roosters, capons, or older hens that no longer laid as many eggs made good fricassee, soup, croquettes stewed chicken, etc. Let’s take a quick look at how they were prepared.

The 18th century cookery book writer Hannah Glasse fricasseed chicken, roasted it, braised it, boiled, pulled it, stewed it, marinated it, curried it, put it in pies and combined it with various other ingredients.

We know Americans love their fried chicken. Numerous 18th and early 19th century cookbooks refer to preparing pigeons just as one did fried chicken, but gave no specific method of frying the chicken, that being commonly known. Numerous books and diaries refer to the joy of travels in Virginia, “where you may dine sumptuously on venison, fried chicken and ham. . .”

Pulled Chickens. 1763.

Take three chickens, boil them just fit for eating, but not too much; when they are boiled enough, flea all the skin off, and take the white flesh off the bones, pull it into pieces about as thick as a large quill, and half as long as your finger. Have ready a quarter of a pint of good cream and a piece of fresh butter about as big as an egg. Stir them together till the butter is melted, and then put in your chickens with the gravy that came from them, give them two or three tosses round on the fire, put them into a dish and send them up hot. She garnished it with lemon.

To Marinate Chickens. 1763.

Cut two chickens into quarters, lay them in vinegar for three or four hours, with pepper, salt, a bay-leaf and a few cloves, make a very thick batter, first with half a pint of wine and flour, then the yolks of two eggs, a little melted butter, some grated nutmeg and chopped parsley; beat all very well together, dip your fowls in the batter, and fry them in a good deal of hog’s lard, which must first boil before you put your chickens in. Let them be of a fine brown, and lay them in your dish like a pyramid, with fried parsley all round them. Garnish with lemon and have some good gravy in boats or basons [sic].

Poulet frit, or, Fried Chicken. 1825

Cut them up; put them into a saucepan with a little parsley and sliced onion, seasoning to your taste, and adding some lemon-juice to make the whole rather acid. Let them steep in this marinade for about two hours, stirring occasionally. When you are ready to serve, drain the chickens, beat up the whites of two eggs, and dip the pieces alternately into the egg and into flour, covering them well; then fry, being cautious that the dripping is not too hot, or the chicken will be burnt and not done through: place the pieces as done on a clean cloth, and send them up dry, with fried parsley, or with a poivrade or tomata sauce.

Poularde à la Duchesse, or, Pullet à la Duchess. 1825.

Put the pullet into a stewpan, with butter, some parsley, green onions and mushrooms chopped fine, salt and pepper; cover it with slices of bacon; moisten with stock, and cook by a slow fire [roast or bake in the oven] when done, take some of the sauce, thicken it with the yolks of eggs over the fire and serve it over the fowl with lemon-juice or vinegar to your taste.

A Country Captain. 1845.

Take a chicken, or any kind of white meat; cut it into pieces, and sprinkle it with salt and pepper, and fry it brown; then add to it three onions, shred small and fried brown, with three spoonfuls of vinegar and four spoonfuls of water; stew it gently until half is evaporated, or boiled away; then add a small sprinkling of curry powder, and dish it up hot.

By: Victoria Brady

Thehistoricfoodie.wordpress.com

Sources Cited:

Orr, James, M.A., D.D. General Editor. “Entry for ‘CHICKEN'”. “International Standard Bible Encyclopedia”. 1915.

“French Domestic Cookery by an English Physician”. 1825.

Bregion, Joseph & Miller, Anne. “The Practical Cook, English and Foreign”. 1845.